About LaTeX, Modes, and Mathtext

![Cover Image for LaTeX: Yes, the one used in _typesetting_ [Part - I]](/assets/blog/latex_1/cover.png)

LaTeX: Yes, the one used in _typesetting_ [Part - I]

Brief Introduction

A significant usage of LaTeX is its ability to handle complex mathematical expressions and keep user-friendliness in mind, primarily combining the simplest of formulas to build a more intricate one. We will discuss how LaTeX typesets math formulas and mathematical fonts.

TeX can tap

into 6 modes – the Vertical Mode, Internal Vertical Mode, Horizontal Mode,

Restricted Horizontal Mode, Math Mode, and Display Math Mode – to help prepare

the document you want.

In this post, we will mostly be discussing mathematical typography and

its construction. (Fun fact: in math mode, LaTeX uses $..$ as math brackets

because typesetting math is supposedly “expensive”).

TeX creates math lists that are composed of the following types of things:

- An atom

- Horizontal or a vertical material (check) (\hbox, \vadjust{kern1pt})

- Glue (\hskip, \mskip)

- Kern (\kern)

- A style change (\displaystyle, \scriptstyle)

- Generalized fraction (\above, \over)

- Boundary (\left, \right) and,

- A four-way choice (\mathchoice)

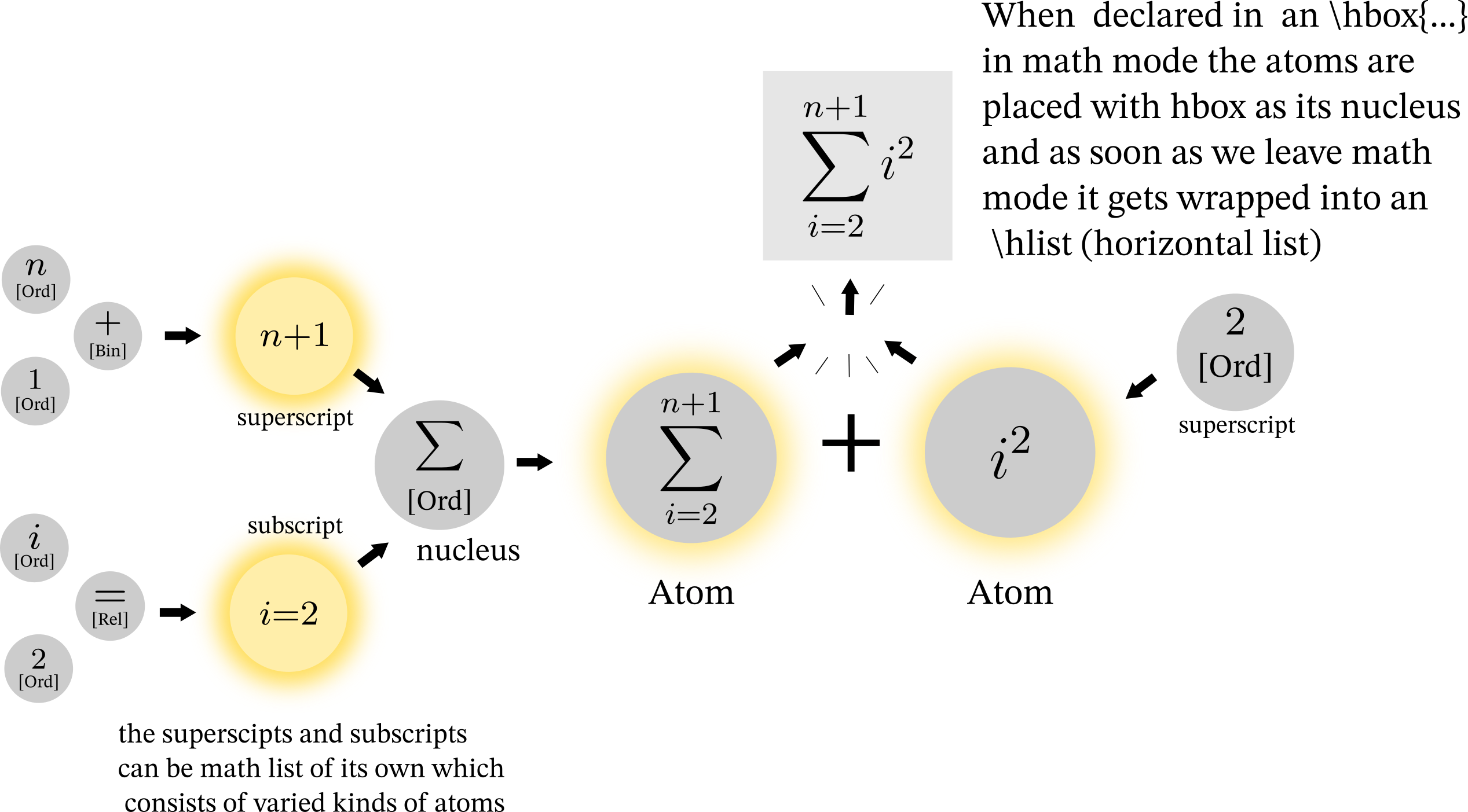

The most important items are called atoms, and they have three parts: a nucleus, a superscript, and a subscript. In TeX, atoms can be one of 13 different types, Ord (ordinary like ‘x’), Op (large operator like summation in the figure below), Bin (binary operator ‘+’), Rel (relational operator ‘=’), Open ‘(’, Close ‘)’, Punctuation, Inner (12), Over (a), Under (a), Accented (à), Radical (√2), \Vcent (Vbox to be centered).

The formula in Fig 1.0 derived from

the latex command: \sum_{i+2}^{n+1} i^2, shows a rough sketch of how

different types of atoms amalgamate together to form subformulas that

further get combined to form the formula we want.

Sometimes LaTeX can get heavy to work with, which is where the mathtext module

comes in. Mathtext can tap into a subset of (La)TeX functionalities without the

huge TeX installation as a requirement to compile math formulas. (Matplotlib

provides the usetex = True option allowing us to access all of LaTeX if

needed.) Mathtext carries out a similar operation to derive the mathematical

typesetting the user requires, However, to put things together while keeping its

aesthetic elements intact, we require some helper functions to skillfully align

and bind everything together.

Boxes, Dimensions, and Glue

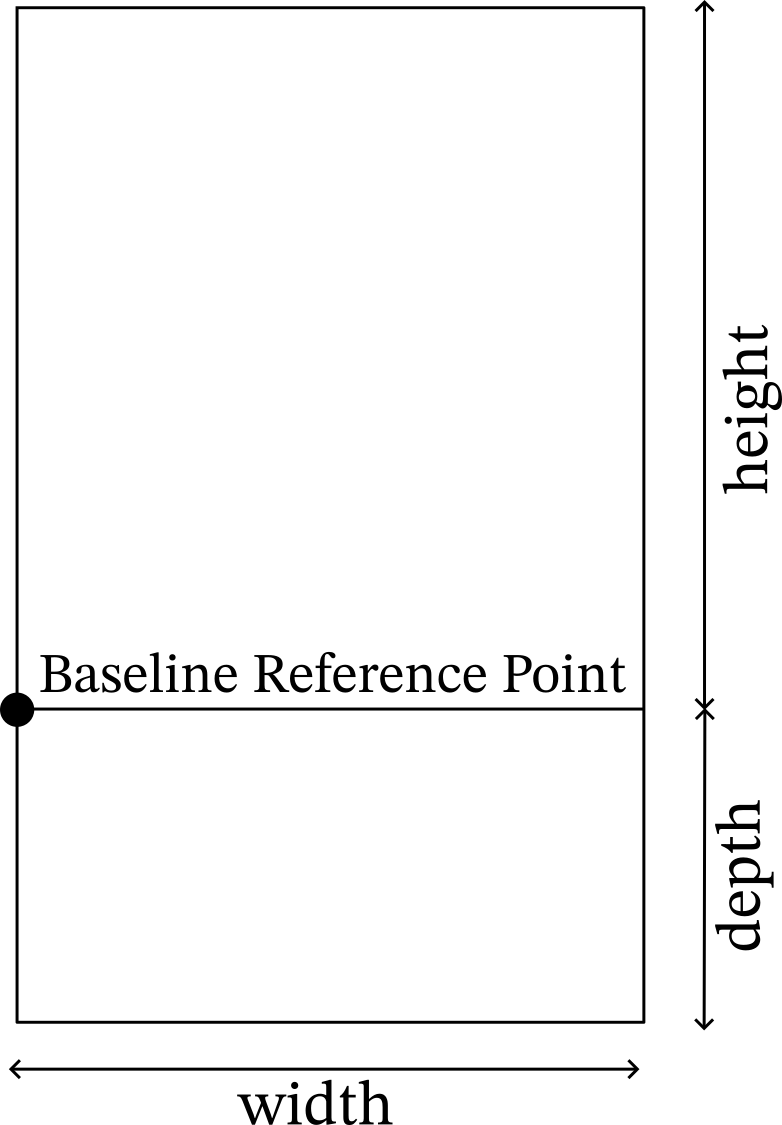

A home for our atoms: boxes that are two-dimensional rectangles with three associated measurements, height, width, and depth. Everything gets constructed nimbly by gluing these rectangles together. The boxes come with a baseline which acts as a reference point in aligning the atoms/characters used in the text or math. These dimensions vary across different fonts. In special cases like using an italic font or a big operator, some of the symbols, extend beyond these measurements. We can also use black boxes (◼) in TeX which are used to create horizontal or vertical lines, notably known as ‘\hrule’ or ‘\vrule’.

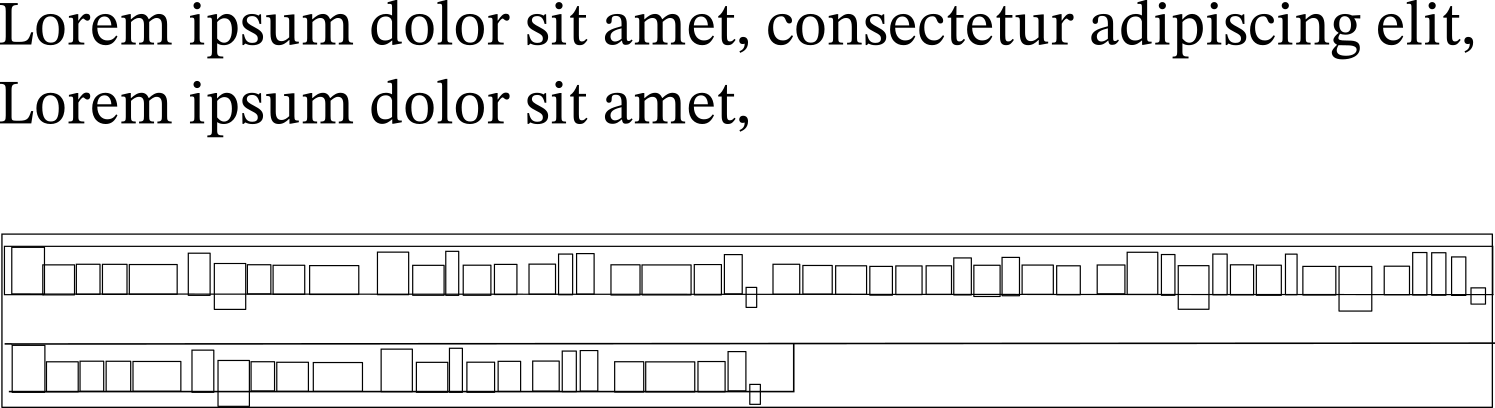

As we see in Fig. 1.3., the characters ‘q’ and ‘t’ appear in the same line, but ‘q’ has a tail end, which gets accommodated in the ‘depth’ to preserve the aesthetics of typesetting. When writing any formula, we wrap the appropriate characters in a box derived from its font dimensions using the ‘\hbox’ command that creates a horizontal box, ultimately gets wrapped inside of a vertical box using the ‘\vbox’ command and the stacking continues until there are boxes stuffed within boxes to form a more prominent box or the page. In TeX’s view, two lines of dummy text would look like this:

Like every crafting project, to achieve the spacing between the lines of text and the spacing between words, TeX uses a “magical” glue to paste these boxes together. This glue can shrink and stretch to keep alignment in order. Glue also comes with its attributes, known as its own space, its ability to stretch, and its ability to shrink. To determine the thickness of the glue, TeX has its own formula to set the stretchability and shrinkability. (Commands used to set glue: \vskip, \hskip, \vfill, \hfill)

The process of determining the thickness of the glue, is called “setting the glue”, and, once set, it loses its magic factors. Another fun fact: Glue was misnamed, because the phenomena discussed above act more as a “Spring” but users liked the term “Glue” so it stayed.